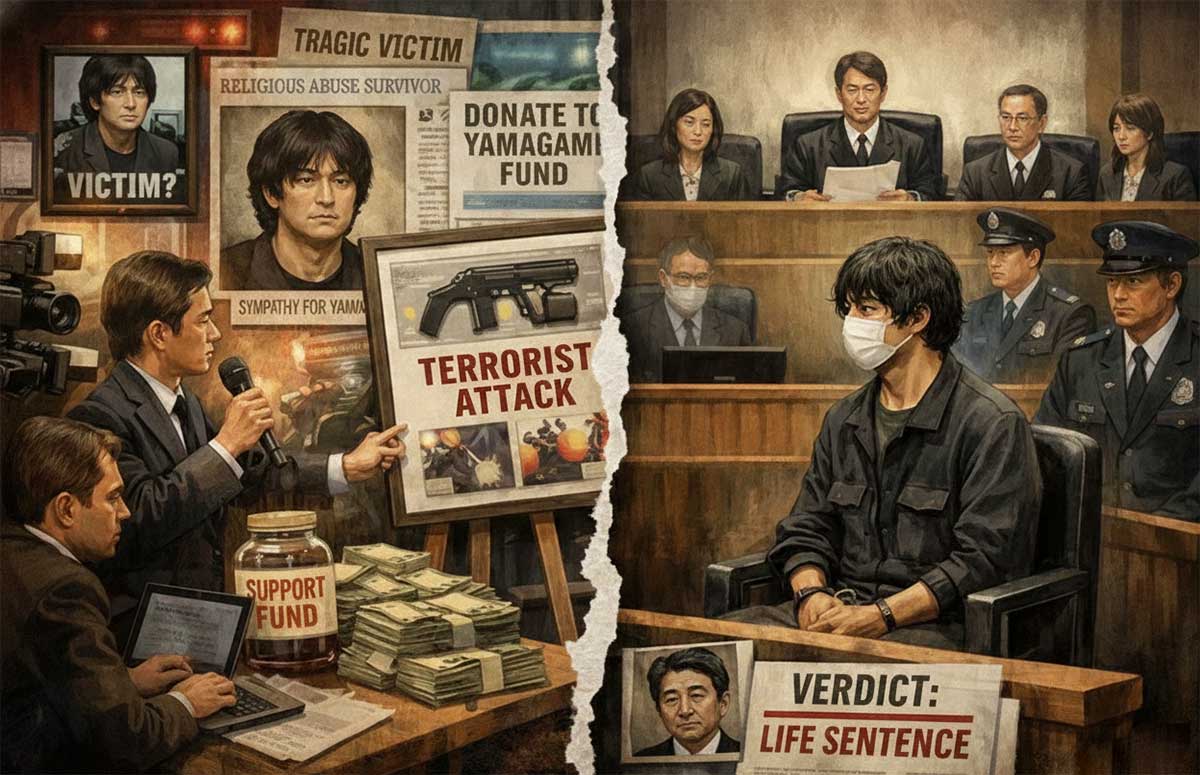

Life sentence in Shinzo Abe assassination case shatters dominant media narrative of assassin Yamagami as a victim

Tokyo, 23rd January 2026 – Published as an article in the Japanese newspaper Sekai Nippo. Republished with permission. Translated from Japanese. Original article.

Religious Harm Created by a Narrative

The Truth and Fiction of Defendant Yamagami

by Seisaku Morita (森田 清策)

prepared by Knut Holdhus

In accordance with the prosecution’s demand, the court handed down a sentence of life imprisonment to Tetsuya Yamagami (山上徹也 – 45), the defendant in the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (安倍晋三). Because the brutal act of killing a globally known political figure with a homemade gun could not be directly linked to the defendant’s upbringing, the court imposed the harshest punishment short of the death penalty.

The significance of this ruling is profound for the media industry. It demonstrates a major discrepancy between the image of Yamagami that was disseminated through media coverage – portraying him as a “victim” of religious abuse who attracted not only public sympathy but even financial support – and the judgment reached by the judge and lay judges based on evidence and testimony presented in court. As a result, the truthfulness and responsibility of media reporting are now being called into question.

The spread of what could be described as a “fictional image” of Yamagami was fueled by journalists’ lack of understanding of religion and by the presence of certain core anti-religion activists. However, even without deep expertise in religious matters, it is possible to approach the reality of Yamagami himself and the true nature of the incident by sincerely engaging with objective facts.

Before the verdict, two essays that sought to examine the case more objectively – distinct from mainstream newspaper and television reporting – appeared in monthly magazines. These were “Courtroom Observation Notes on the Assassination of Former Prime Minister Abe,” by lawyer and journalist Hitofumi Yanai (楊井人文 – Hanada, January-February issue), and “The Deep Darkness of the Yamagami Family,” by writer Fumihiro Kato (加藤文宏 – Seiron, February issue).

Including the sentencing, the trial was held a total of 16 times. Of the 14 sessions held up to the time of writing, Yanai attended all but two, from which he was excluded due to the lottery system. He cited two reasons for doing so. First, he wanted to witness firsthand how judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and lay judges would confront, deliberate upon, and adjudicate the historic case of a former prime minister’s assassination.

The second reason was his discomfort with the widespread narrative portraying Yamagami as someone whose life was destroyed along with his family by the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Family Federation, formerly the Unification Church), which his mother joined and to which she made large donations. Yanai felt uneasy that public attention had shifted away from the incident itself toward “the relationship between the former Unification Church and politics.”

What Yanai emphasized in the January issue was that the incident was a premeditated act of terrorism carried out by Yamagami. A police officer who testified in court stated that when searching Yamagami’s room, it “felt like a terrorist’s hideout,” and prosecutors explained that, in addition to the weapon used at the crime scene, six homemade pipe guns were discovered. Based on these facts alone, it can be stated unequivocally that Yamagami was a terrorist.

Meanwhile, Kato’s essay was written based on interviews with a former church leader, identified as Mr. A, who had supported the Yamagami family and was trusted by the defendant. Out of gratitude to Mr. A, who had shown concern especially for his older brother, Yamagami even gave him a pair of sneakers as a gift. The essay also revealed that the decision by the religious organization to refund 50 million yen of the 100 million yen donated by Yamagami’s mother was agreed upon by all three siblings, including Yamagami himself.

The media reported as though the Yamagami family collapsed solely because the mother adhered to the Family Federation’s faith. However, when Yanai’s February article and Kato’s essay are considered together, a different reality emerges: prior to the mother’s religious involvement, the family had already suffered severe hardships, including the father’s suicide and the eldest brother’s illness. It was likely that the mother sought salvation from these misfortunes.

“The mother did not force her faith on her children,” Kato writes. The notion that Yamagami had been a victim of religious abuse from early childhood can thus be seen as a narrative constructed on the basis of prejudice against religion.

That said, this does not mean the Family Federation was entirely unrelated to the family’s hardship. Mr. A explained that the mother attended a church originally intended for Korean members, which often resulted in a lack of understanding of Japanese culture and family norms – factors that contributed to the large donations. Nevertheless, this was not a direct cause of the terrorist act.

By intentionally focusing media coverage on Yamagami’s motives, the violent act itself was rendered ambiguous as an act of terrorism. Furthermore, issues involving the religious organization, which were at most a remote contributing factor, were substituted as the primary cause, resulting in a reversal whereby the perpetrator was cast as a victim and the victims as perpetrators. However, the life sentence handed down makes clear that the facts established in court were far removed from the narrative spread through biased reporting. Going forward, the question society must confront is whether it can accept that reality.