When lived faith brings change ‒ Why real-world religion easily becomes an issue, making some feel uneasy

Prepared by Knut Holdhus

Modern discussions of religion often assume that faith belongs primarily to the private sphere: beliefs held in the mind, rituals practiced in designated spaces, and moral principles applied individually. In an article headlined “Why Do ‘Event Religions’ Always Become Controversial?” in the South Korean daily Segye Ilbo 13th January 2026, religious affairs correspondent Jeong Seong-su points out that when religion stays within those boundaries, it is generally tolerated ‒ even when its doctrines are unusual or demanding.

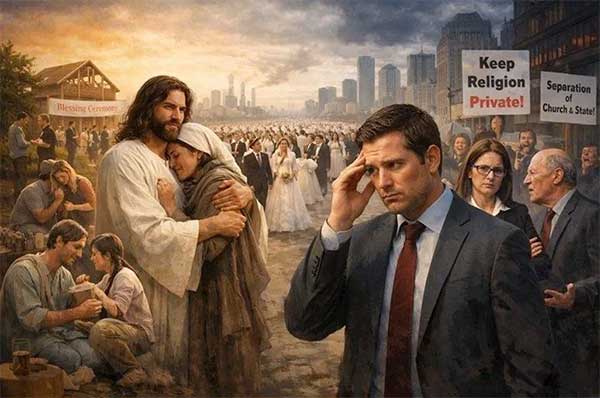

Problems tend to arise, however, when religion moves beyond belief and attempts to reorganize everyday life, social relationships, and public order. Jeong’s opinion piece addresses this precise tension by introducing a distinction that is rarely made explicit in Western discourse: the difference between “doctrinal religion” and what the author calls “event religion”. The headline asks why religions that insist on realizing their truth in real historical life (“event religions”) ‒ rather than remaining as abstract beliefs (doctrinal religions) ‒ inevitably provoke controversy and social resistance.

The Korean expression translated as “event religion” ‒ 사건 종교 ‒ means a religion that grounds its truth in historical action, seeks realization in lived reality, and demands social, relational, or structural change.

According to the article, religions follow one of two broad paths. Some remain primarily as doctrines ‒ systems of belief, theology, and moral teaching that people accept, debate, or reject intellectually. Others originate as events: concrete historical interventions that do not merely propose ideas about how life should be lived, but attempt to demonstrate and embody those ideas within the real world. An “event religion” does not remain content with faith as inner conviction; it insists on manifesting itself through relationships, families, social structures, and history itself. And for precisely that reason, the author argues, event religions almost always become controversial.

This controversy is not caused by irrational belief or theological impurity. On the contrary, the problem is that event religions are very realistic. They intrude into areas that societies tend to guard carefully: marriage, family formation, authority, lineage, social norms, and collective identity. Historically, many of the religions now regarded as established traditions began as event religions.

The early Jesus movement before Christianity became an institution, the Exodus faith of ancient Israel, early Buddhism, and Islam all began not as abstract philosophies but as lived historical disruptions. They demanded change not only in belief, but in how people organized their lives together. Societies, the Segye Ilbo article suggests, have always found this unsettling.

The figure of Jesus is central to this kind of argument. From this perspective, Jesus was not primarily a teacher of doctrine or a founder of an organized religion. He did not leave behind a systematic theology, a legal code, or an ecclesiastical structure. Instead, his message was embodied in how he lived: radical love without resentment, forgiveness without conditions, and ethical action focused on the present rather than rewards in the afterlife. Jesus did not explain his vision in theoretical terms; he enacted it.

Yet this way of life, the article emphasizes, remained historically unfinished. Jesus did not establish a family, leave descendants, or stabilize his movement within existing social structures. His execution ended the event without bringing it to completion. What followed, therefore, was not simply continuation but reinterpretation. That role fell to the apostle Paul.

Paul, who never met Jesus during his lifetime, transformed what appeared to be historical failure into theological success. The crucifixion was reframed as a necessary condition for salvation rather than a defeat. The unfulfilled hopes of history were redirected toward the afterlife. This reinterpretation allowed Christianity to survive, spread, and eventually become a world religion. However, it also fundamentally changed the nature of the movement. The life of Jesus ceased to be primarily a path to be followed and became instead a doctrine to be believed. The disruptive “event” was sealed into a manageable belief system. In the language of Jeong’s article, Christianity ceased to function as an event religion.

This transition is where the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) enters the discussion. Nietzsche’s famous critique of Christianity, the article argues, was not aimed at Jesus himself but at the religion that developed after Paul. Nietzsche saw Christianity as a moral system that glorified weakness, suffering, and failure. Yet paradoxically, he held a certain respect for Jesus as a human figure ‒ someone who lived without resentment, deferred judgment, and affirmed life in the present moment. This is why Nietzsche has sometimes been called “the thirteenth disciple”: while the institutional Church preserved Jesus as doctrine, Nietzsche sought to destroy that doctrine in order to recover the vitality of Jesus’ life and movement.

According to religious affairs reporter Jeong, Nietzsche’s declaration that “God is dead,” from this viewpoint, was not a simple rejection of faith. It was a diagnosis: a statement that what had once been a living, transformative event had hardened into lifeless dogma. Still, Nietzsche’s critique stopped at exposure. He could explain why the original event failed, but he could not offer a practical way to reestablish such an event within history.

The article then turns to the Family Federation, formerly the Unification Church, as a radically different response to this dilemma. Unlike mainstream Christianity, the Family Federation does not view the crucifixion as the completion of salvation. Instead, it is understood as an unfinished historical moment ‒ something that must still be fulfilled in human society. Salvation, in this framework, is not primarily about individual belief or personal redemption after death. It is about the restoration of relationships, families, and social structures in the present world.

Central to this vision is the idea of the “True Parents”, figures who complete what Jesus could not by forming a family and establishing a lineage centered on goodness. In this model, salvation becomes something that must be verified within history rather than merely affirmed by faith. It is no longer enough to believe correctly; the truth of the religion must be demonstrated through lived, social reality.

This is where the Family Federation fully embraces the burden of being an event religion. Its most visible and controversial practice ‒ the Marriage Blessing ‒ is not presented merely as a religious ritual but as a means of restructuring human relationships around the ideal of “one human family under God”. When such practices aim to extend beyond a single religious community and propose a universal social order, tension is inevitable. Religion, at that point, stops asking only for belief and begins to challenge how society itself is organized.

The article makes a striking claim at this juncture: if an event religion truly succeeds, it should eventually disappear as a religion. Once its core structures are established in reality ‒ true families, restored lineages, stable social patterns ‒ there is no longer a need for ongoing doctrinal expansion or religious instruction. According to Jeong, authority does not pass endlessly from leader to leader; it is fixed in the structure that has already been realized. Subsequent leadership exists to manage, not to recreate, the original event.

From this perspective, controversy surrounding the Family Federation is not accidental or merely the result of misunderstanding. It is structurally inevitable. Any religion that insists on embodying salvation within real human life must accept constant scrutiny, criticism, and the risk of failure. Event religions have no right to remain comfortable or unchallenged.

Jeong’s article concludes with a clear thesis: event religions become problematic not because they are false, but because they are so real. The path of the Family Federation is difficult not because it rejects society or seeks attention, but because it refuses to reduce salvation to words, doctrines, or explanations. It attempts, instead, to complete salvation through lived human experience. And that, the author suggests, is precisely why it provokes unease ‒ and why it cannot avoid controversy.