By David Eaton

In the current iteration of the so-called “culture wars,” a primary narrative deals with the debate between those advocating a socialist modality and those advocating free-market capitalism. Unificationists have been debating the pros and cons of these modalities as well.

The 1996 Exposition of the Divine Principle references (p. 342) the Welsh socialist pioneer Robert Owen (1771-1858) in the context of establishing a culture predicated on the ideals of interdependence, mutual prosperity and universally shared values. As Divine Principle notes, our original mind and our “inmost hearts,” aspire to “the world of God’s ideal where the purpose of creation is fulfilled.”

Though Divine Principle characterizes Owen’s brand of socialism as “humanistic,” his attempts at striving for fairness and equality tend to be in accord with what might be termed, “heavenly socialism” in the context of achieving mutual prosperity.

Regarding capitalism from a God-centered perspective, we read from our founder, Rev. Sun Myung Moon, in Book 10 of Cheon Seong Gyeong:

“If America is armed with Godism, rooted in Headwing thought, Godism and free-market capitalism will become like inner and outer halves. Then, through my guidance America can progress in a perpendicular line straight toward God.”

This statement may seem to be at odds with Divine Principle’s reference to a society predicated on heavenly socialism, however, our founder defines the “-ism” in Godism as “the way of living.” Thus Godism ought to apply to all human endeavors — politics, education, commerce, journalism, and the arts and sciences. Book 10 of Cheon Seong Gyeong also emphasizes the importance of the Three Blessings as described in Genesis as the basis for a culture predicated on Godism.

Robert Owen and the Early European Socialists

I confess I didn’t know much about Robert Owen until recent debates regarding the merits of socialism with other Unificationists prompted me to investigate. Owen and early European socialist advocates, Sylvain Maréchal (1750-1803) and François-Noël Babeuf (1760-1797), pre-dated Karl Marx by several decades. Like Marx, their primary focus was on the question of how societies should live in a fair and equitable manner as the old feudalist modalities were giving way to the new ideas of the Enlightenment vis-à-vis individual rights, free markets, laissez faire economics, and private ownership.

Critic and commentator, Roger Kimball, has noted that the early socialist paradigms were not primarily economic modalities, but rather focused on socio-cultural issues, especially with regard to fairness and equality. Kimball cites Babeuf’s disdain for the privileged “bourgeoisie” class and his advocacy for a “conspiracy of equals” that could put an end to “bourgeois normalization.”

Owen established several socialist communes in Scotland and the United States in the early 19th century. These efforts were his response to the widespread poverty in Britain after the Napoleonic Wars. One of his most ambitious communes was established in New Harmony, Indiana, on the banks of the Wabash River in 1825.

Central premises of what came to be known as “Owenism” included communal living, charity, fair exchange of goods and services, and better working conditions for laborers and children. Owen was apolitical, but he became a major influence in the formation of trade unions in Britain and the United States. He was one of the first proponents of an eight-hour workday.

However, due to various internal conflicts within the commune, the New Harmony enterprise dissolved in 1827. These conflicts included religious disputes and lack of adequate housing and resulted in lawsuits and several schisms within the commune. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Owen lost 80% of his wealth in the New Harmony project — £40,000 ($1.1 million in today’s dollars).

This begs the question: How did Owen attain the funds that financed his investments in these socialist experiments?

As it happens, Owen generated income from a successful textile mill, New Lanark, in Scotland, which he inherited through his marriage. He used the profits from New Lanark to finance the New Harmony project as well as his other communes. It was via a capitalist enterprise that Owen acquired enough wealth to invest in these communities. At one point, the New Lanark mill had between 2,000 and 2,500 employees.

Though Owen did quite well in his business ventures, his socialist experiments were another matter. Like Maréchal, Babeuf and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), Owen believed that human nature could be molded in ways that could mitigate vice and foster virtue. Being a utopian idealist, his advocacy for economic equality in economic matters can be viewed as being virtuous. Owen’s views led him to “socialism,” a term some scholars believe he introduced to the English-speaking world. In 1826 he made this query:

“Is it not the interest of the human race, that everyone should be so taught and placed, that he would find his highest enjoyment to arise from the continued practice of doing all in his power to promote the well-being, and happiness, of every man, woman, and child, without regard to their class, sect, party, country or colour?”

This perspective is one Unificationists would wholeheartedly embrace. It’s a call for unity and getting beyond that which is divisive and destructive. However, Owen was not an advocate of certain ideals espoused in Divine Principle, especially regarding Godism and the Three Blessings. In a speech he gave at New Harmony entitled, “A Declaration of Mental Independence,” Owen rejected several central premises of Divine Principle. He would say:

“I now declare, to you and to the world, that Man, up to this hour, has been, in all parts of the earth, a slave to a trinity of the most monstrous evils that could be combined to inflict mental and physical evil upon his whole race. I refer to private, or individual property, absurd and irrational systems of religion, and marriage, founded on individual property combined with some one of these irrational systems of religion.”

By characterizing religion and marriage and the understanding of the incorporeal realm via religious belief — foundational aspects of a God-centered culture — as “monstrous evils,” Owen essentially paved the way for the failure of his otherwise noble efforts. This points to the importance of people living in socialist modalities needing to have shared values and a God-centered motivation in establishing a “community of equality.” Though Owen was not an atheist, he nonetheless had serious contempt for certain ideals necessary to create a society predicted on Godism.

Owen’s views regarding the transformation of human nature were similar to those of Rousseau, who espoused the idea of an imagined past in which humanity was not subjected to the rapacious and predatory impulses of a corrupt and mendacious upper class. As Rousseau famously put it, “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains.” For Rousseau, “changing human nature and transforming the individual” to align with egalitarian premises was both necessary and possible. The question of how to accomplish this transformation in an efficacious manner remains salient.

In his co-authored Manifesto of Equals, written in 1796 in the aftermath of the French Revolution, Maréchal, a self-proclaimed “man without God,” wrote: “If there is a single man on earth who is richer and more powerful than his fellows, then the equilibrium is broken: crime and misfortune are on earth,” and it was imperative to “remove from every individual the hope of ever becoming richer, or more powerful, or more distinguished by his intelligence.”

Moreover, Maréchal, called for “the disappearance of boundary-marks, hedges, walls, door locks, disputes, trials, thefts, murders, all crimes, courts, prisons, gallows, penalties, envy, jealousy, insatiability, pride, deception, duplicity, in short, all vices.” To accomplish these goals he hoped “the great principle of equality or universal fraternity, would become the sole religion of the peoples.”

This echoes Marx’s idea of “humanism,” replacing religious belief (“the opiate of the masses”) as the necessary step to attain equality. It also predates Michel Foucault’s supposition that prisons were perhaps the greatest affront to a person’s freedom and dignity because the distinction between a convicted criminal and the power structure of law enforcement was both severe and discriminatory.

That said, I dare say most people would like to see a society where “all vices” would disappear and a “universal fraternity” would take shape. But without implementing Godism via the Three Blessings, that’s just not happening. Robert Owen’s socialist experiments are a case in point.

Choice and Free Markets

In a 2006 essay titled “Shopping in Cheon Il Guk,” in the Journal of Unificationist Studies, Tyler Hendricks makes the point that entrepreneurial activities need to be rooted in principled motives and intention. This is a point I often make regarding the creation of a work of art. What an artist creates and puts before the public has consequences, thus motive and intention ought to be informed by values based on Godism. This axiological concern relates to the “goodness” aspect in the beauty/truth/goodness paradigm and what we choose to create.

In referring to the matter of choice, Dr. Hendricks writes:

“In Cheon Il Guk, we are talking about the ideal society made up of selfless people. Will it be capitalist? Well, can selfless people go shopping? Can they engage in transactions, choosing what they like, expressing preferences, and trying to get higher value for less cost? These things sound selfish, and without them, the capitalistic system won’t work.”

In this respect, individual choice in relation to the greater good of society is paramount. Adam Smith posited that capitalism has self-purpose and whole-purpose aspects that need to be harmonized and balanced. Making a profit is not intrinsically evil or selfish if the profit is used for a greater good. Our movement has several for-profit enterprises that fund various providential projects. These include the New Yorker Hotel, Manhattan Center, Tongil Construction, Seil Travel, Il Hwa Pharmaceuticals, and the Yongpyong resort and golf course. Money can be used selfishly (greed), or unselfishly (altruism), and these enterprises are examples of the latter.

Regarding “culture wars,” entrepreneur John Mackey, founder of Whole Foods Market, makes the point that the term “capitalism” has been “hijacked intellectually by economists and critics who have foisted on it a narrow, self-serving and inaccurate identity devoid of its inherent ethical justification.” It should come as no surprise that many of these critics are of a pro-socialist persuasion, thus any capitalist enterprise is viewed as being inherently untoward and unjust. This attitude ignores the possibility of altruism and charity being in the capitalist equation.

Saint Augustine averred that people fail because they choose to love the wrong things. For Unificationists, freedom and choice need to be informed by that which is godly and beneficial to the individual and the greater society. This ought to be a primary emphasis of our witness in promoting the ideals of interdependence, mutual prosperity and universally shared values. In the spirit of harmony and balance it would seem that both capitalist and socialist modalities can be beneficial if they are predicated on Godism.♦

David Eaton has been the music director of the New York City Symphony since 1985 and was recently an artist-in-residence in Korea serving as the Director of Music at the Hyo Jeong Cultural Foundation and conductor of the Hyo Jeong Youth Orchestra. He received an honorary doctorate from Unification Theological Seminary (now HJ International) in 2016.

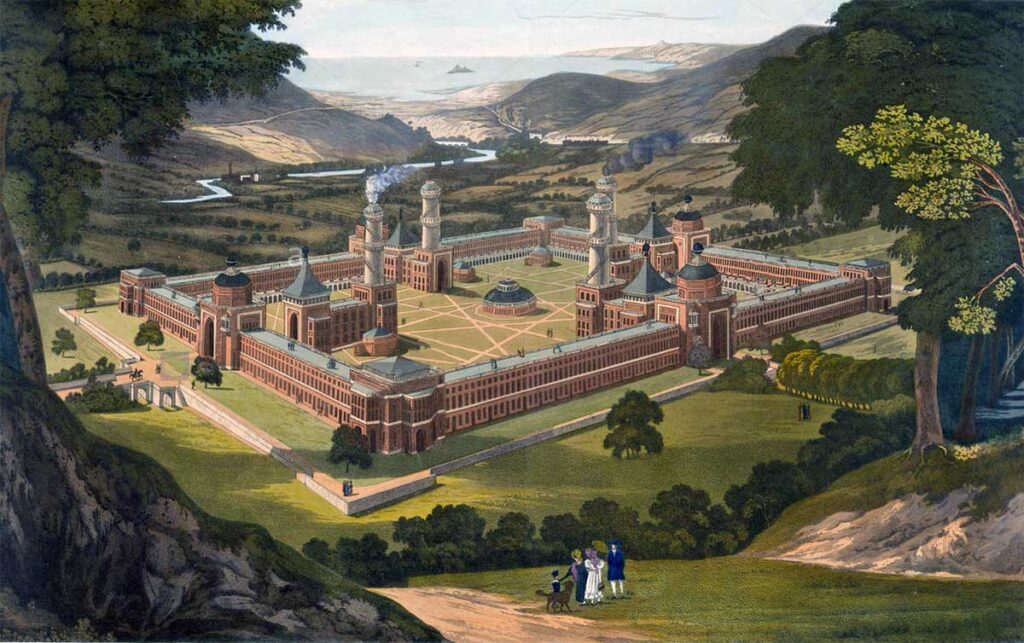

Painting at top: “Portrait of Robert Owen” by W. H. Brooke.

Listen to this text using the NaturalReader Google Chrome extension. Download it here.